Baldé finds his roots in West African Guinea

On a blistering, hot February day in Africa, Elladj Balde looked into the eyes of his 99-year-old grandfather for the first time and discovered who he really was.

Balde, 24, had never set eyes on his grandfather, Elhadj Mamadou Oury Balde, who is an imam in Tombon, a tiny village in the mountains of Guinea in West Africa, a town where there is no electricity or running water, cattle and goats wander everywhere and the good folk of the town grow their own food. Need some water? Grab a bucket, lower it into a deep hole, pull it back up and good luck.

Mind you, there is no pollution in this remote village, largely untouched by the development of civilization and big businesses. It’s nature at its purest. Everywhere there were banana trees, mango and orange trees. “It is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen,” Elladj said.

Yes, Elladj is named after his grandfather, because after all, he’s the first son of his father, Ibrahim, who was the first son of Elhadj, all highly emotional and critical points in this culture.

This brings us to the grandfather, the reason for this unprecedented pilgrimage that was taken despite Government of Canada warnings to avoid travel to Guinea, the epicenter of the Ebola crisis that erupted in 2014. There were also security advisories, warning of political, social and economic unrest, rampant corruption, rebel activity and armed robberies, particularly if you travel to outlying areas. Still, Elladj and his father had to go.

As an Imam, Elhadj was a man of renown, not only in Tombon but also in all of northwest Africa, as the priest of the mosque, the teacher of young Imams, the holy man. So exalted was his status, that convention dictated a holy reserve: Elhadj didn’t hug people like figure skaters do. He was untouchable.

His firstborn son, Ibrahim, had much to live up to, and he did. From age four, he was always at the top of his class. Being tops meant that you received support to go to the next level. When Ibrahim finished first in his university class in Guinea, he earned an expenses-paid scholarship to the Soviet Union, Tashkent actually, which is now the capital city of an independent Uzbekistan.

Ibrahim was given six months to learn the Russian language, and applied himself the way he always had. While studying medicine, he was tops in his class once again. (Elladj remembers his father urging him always to do hours and hours of homework, and when he’d finish an assigned chapter, to read the next one too. “You always have to be ahead of the rest,” he said. Elladj said he has inherited his father’s drive.)

Ibrahim met and married Marina, who was studying meteorology in the Soviet Union, and they had a daughter, Djulde, who at age seven, fell ill with leukemia. Elladj was born in Moscow and when he was only one year old, the family moved to Bonn, Germany to get medical help for his older sister. A year later she died. But the young family had a difficult decision to make: how could they return to the Soviet Union which, in the meantime, was disintegrating, as well as perhaps Ibrahim’s scholarship? And they just didn’t feel it was safe to return.

So off to Canada they went and settled in Montreal, a world away from Guinea. Still, Elhadj’s fondest wish was to see his grandson, Elladj, before he died. However in December, he fell into a coma and it appeared too late.

Miraculously, two weeks later Elhadj awakened from his coma. It was then that Ibrahim knew he had to travel to Guinea to see him one more time. He booked his flight immediately to leave Feb. 22.

Elladj begged him to wait, because at the time, he had nationals coming up, and he had hoped to go to Four Continents and the world championships in February and March. But Ibrahim could not wait. “I don’t know how long he is going to live,” he said.

At the Canadian championships in Kingston, ON, all of Elladj’s skating dreams fell apart. He finished sixth and not only missed a trip to the World and Four Continents championships, but he lost a spot on the national team with all of its funding.

However there was a bigger issue on his mind. The day of his disastrous long program, Elladj booked his flight to Guinea. “I’m coming with you,” he told his father. “I’m a strong believer that everything happens for a reason.”

Many, including doctors, warned Elladj not to go, because of Ebola. Elladj finally reasoned: “If I die of Ebola, then I’m meant to die of Ebola.”

It was a long, exhausting and expensive journey. The Baldes flew from Montreal to Paris and then to Guinea’s capital city of Conakry. When they deplaned, 50 people from Tombon – all relatives (Ibrahim has 29 siblings who are still alive; his father had four wives), all-weeping with joy. Somehow, despite their remote location, they had heard of this figure skater with a Guinean name. They had followed him. Elladj also met the Minister of Sport in Guinea.

Their journey wasn’t over yet. It took 10 hours to drive to Tombon. They drove up into the mountains where there were no roads, only rocks. For two hours, they couldn’t go faster than 5 miles per hour.

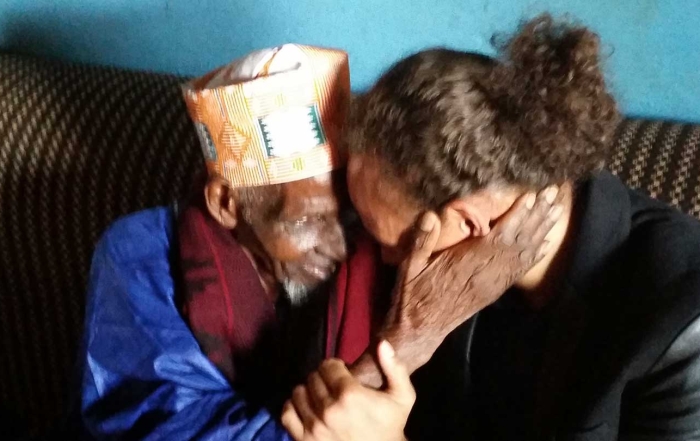

Finally in Tombon, Elladj sat down in the house of his grandfather and this man who never hugs anybody, took Elladj’s face in his hands, exclaiming: “Thank you god. Thank you god.” Over and over again. “It was one of the best moments of my life,” Elladj said. “We held each other for a long time, maybe five minutes.”

Others were looking on in shock, at the Imam’s embrace. “I can die in peace now,”said Elhadj, frail of heart, but sharp of mind. “God can take me.”

“He was so proud of who I was,” Elladj said. “As a human being, not as an athlete. He was so happy for who I was and what kind of person I am. I realized so many things.”

The 11-day experience in Tombon has changed Elladj forever. They were happy people, although they had little. “It changed me deep inside,” he said. “It does something to you that you don’t expect. It was the best experience of my life.”

In May, Elladj’s grandfather died.

He knows now what really counts. His relationships with his family have changed. He’s back at home in Montreal, now living with his parents and training with Bruno Marcotte and Manon Perron. His skating has changed, because now he appreciates his opportunities in life. (He has a cousin in Conakry who has been looking for a job for six years.) He now skates with joy.

Elladj’s African experience, he says, has rooted him to the ground. He’s become part of the world, of its nature. He saw the origins of time, where his blood had come from and finds family ties are powerful. “At the end of the day, we are not so different,” he said. “We all strive for happiness. And it’s all that matters.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!